BACK PAIN

back pain is extremely common human phenomenon ,a price mankind has to pay for their upright posture. almost 80% of persons in modern industrial society will experience back pain at some time during their life .

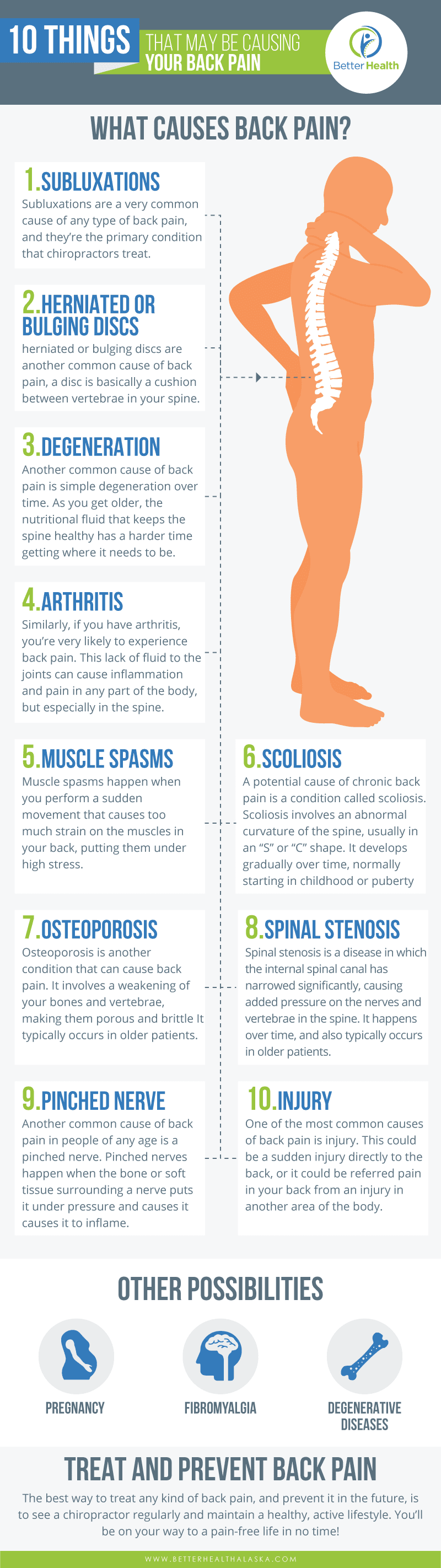

causes

|

FEATURE OF PAIN |

- LOCATION : Pain may be located in upper middle or lower back. disc prolapse and degenerative spondylitis occur in the lower lumbar spine ;infection and trauma occur in the dorso-lumbar spine.

- ONSET:there is history of significant trauma immediately preceding an episode of back pain,and may indicate a traumatic pathology such as a fracture ,ligament sprain muscle strain etc.

- LOCALISATION OF PAIN :pain arising from a tendon or muscle injury is localized ,whereas that originating fron the deeper structure is diffuse. often ,pain referred to a dermatome of the lower limb ,with associated neurological signs pertaining to a particular root,point to nerve root entrapment.

- PROGRESS OF PAIN :in traumatic conditions,or in acute disc prolapse ,pain is maximum at the onset,and then gradually subsides over days or weeks back pain due to disc prolapse often has period of remissions and exacerbations . an arthritic or spondylitic pain is more constant,and is aggravated by activity .pain due to infection or trauma takes a progressive course ,with nothing causing relief .

LOW BACK PAIN

BIO-MECHANICAL FACTORS

Instead of being straight, the spinal chain assumes a typical curvacious posture. It has two lordotic curves at the cervical and lumbar spinal segments and a kyphotic curve at the dorsal region. These postural adaptations which occur under the impact of the gravitational force play a significant role in the distribution of the weight of the bony structures and the organs from head to pelvis besides offering free spinal mobility. The role of lumbar lordosis in reducing the LBP is well recognized.

Daily activities put tremendous repetitive, compressive and shearing stresses on the bony components of the back, and tensile stresses on the muscular and ligamentous components. The shearing stresses on the intervertebral ligament and the apophyseal joints of the lumbosacral junction are proportional to the angle formed by the superior surface of the sacrum with the horizontal surface. At a normal sacral angle of about 40 degrees, the shearing force is 65% of the superincumbent weight (Fig. 32-34A). This shearing force increases if the anterior tilt is increased,

https://telegram.me/aedahamlibrary

and diminishes when the back is flattened (Figs 32-34B and C). Therefore, a protective spasm of extensors occurs following strain which flattens the lumbar curve to diminish the shearing stress.

Intervertebral discs act as shock absorbers and provide hydraulic resistance to motion under high pressure. The lumbar spine is mounted on the sacrum at an angle of 45 degrees and is always eccentric in position, needing some external support for balance. This position produces larger shearing force on the lumbar spine. Maximum strain occurs on the lumbar ligaments during flexion. Greater activity from the lumbar spine results in variations in the intradiscal (ID) pressure. Nachemson (1966, 1976) and Nachemson and Elfastrom (1970) reported data on intradiscal pressures in different postures, activities and exercises. It is extremely important to understand the extent of load on the spine in different situations to guide and plan the precise therapeutic programme (Tables 326–32-8).

Active trunk flexion from the supine position raises intradiscal pressure tremendously. Intradiscal pressure of 100 kg during standing rises to 280 kg. Similarly, active hyperextension raises the intradiscal pressure to 180 kg. This needs due consideration before initiating these exercises.

Examination of posture

The normal physiological postural curves and gait should be observed from the front, back and the side.

Assessment of pelvic tilt: Deviation from the normal angle of pelvic tilt is assessed in standing position. The tilting of the pelvis could be anterior, posterior or lateral.

Anterior pelvic tilt: The anterior tilting of the pelvis may occur as a result of the protruding abdomen (e.g., in obese people), tight low back muscles, tight hip flexors, weakness in the abdominal muscles, tight hamstrings or in spondylolisthesis. When present, it puts excessive pressure on the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies and the facets, as there is exaggeration of the lumbar lordotic curve. Posterior pelvic tilt: Posterior tilt may result from tight or overdeveloped low back muscles. Weakness of hip flexors (psoas) or localized muscular spasm may result in the obliteration of normal lumbar lordosis into a flat back. Lateral pelvic tilt: In lateral pelvic tilt, the pelvis drops on one side. It could be due to limb length disparity, unilateral lumbosacral strain, structural scoliosis or scoliosis due to unilateral muscular spasm. Reasons may also include muslce imbalances, such as weakness of gluteus medius, with strong hip adductors and lateral rotators on the raised side of the pelvis, with tightness of the adductors and TFL on the opposite side or unilateral PIVD.

Objective measurements of pelvic tilt: Anterior and posterior pelvic tilts are measured on a radiograph lateral view. The angle formed by a line parallel to the superior level of sacrum with the true horizontal line is measured. The normal angle is in the vicinity of 30 degrees. It increases in the lordotic curve (Fig. 32-34). Lateral pelvic tilt is objectively measured by measuring leg length when there is discrepancy in one leg. It can also be assessed by measuring the difference in the true horizontal line and the horizontal

https://telegram.me/aedahamlibrary

line passing over the tips or the bony prominences of anterior or posterior iliac spines.

Range and rhythm of the spinal movements

The movements of the lumbosacral complex include basically the movements at the intervertebral joints of the lumbosacral spine and the synchronized movement or stabilization of the pelvis in relation to the hip joint. The principal movements to be examined at the lumbosacral complex are flexion, extension, lateral flexion and rotation to either side.

Characteristics of movements

The aim is to reproduce the patient’s symptoms by doing movement or by appropriate joint sign. Normally the movement should be of full range and pain free with overpressure. Sometimes sustained test for extension, lateral flexion and quadrant test towards the symptomatic side may be required to reproduce the symptoms. The movements are tested as active ROM, resistive (isometric) small arc movements and passive movement with overpressure at the terminal range. Besides these, passive accessory intervertebral movements are tested at the early, mid and late ranges to elicit the ‘joint sign’. A ‘joint sign’ is an alteration in active, passive, physiological or accessory joint mobility relative to pain, resistance or spasm which limits the ROM of the joint. The joint sign helps in detecting the exact vertebral level involved and also the status of the passive mobility of the intervertebral joints. The restriction of active range indicates segmental soft tissue inflexibility of the functional units, facet capsules, ligaments and fascia. Resistance to movement will produce pain in the musculotendinous lesions. Pain on passive movement will produce compression in the joint – producing pain due to joint pathology or nerve compression. Application of overpressure also increases pain at the site of the lesion and increased radiation.

https://telegram.me/aedahamlibrary

To find out the appropriate structures related to pain, the symptoms should be reproduced by performing movement enough to the point of first increase in symptoms.

Flexion (lumbar pelvic rhythm): It is tested by asking the patient to bend forward (toe touching) from stride standing without bending the knees. The movement involves synchronized movement of flexion at the intervertebral joints of the lumbar spine and rotation of pelvis around the hip joint. In this rhythm the lumbar lordosis gradually flattens and turns into a kyphosis at the terminal range of flexion (Fig. 32-37). This puts tremendous amount of compressive force and load on the anterior vertebral margins with opening up of the posterior vertebral margins. https://telegram.me/aedahamlibrary

FIG. 32-37 Normal lumbar pelvic rhythm showing the normal lumbar lordosis turning into a kyphosis at the terminal range of flexion and its measurement by sliding ruler arrangement. The restriction of flexion indicates the soft tissue inflexibility at the lumbosacral complex and/or pelvis due to protective reflex spasm from pain or guarding (tightness of hamstrings could also result in altered rhythm). Occasionally, trunk flexion may be associated with rotation to one side. This indicates the presence of structural scoliosis, indicating

lumbosacral facet tropism. It may be limited to the hip joint, the lumbar spine remaining rigid as in ankylosing spondylitis. Persistence of lumbar lordosis instead of kyphosis at the terminal range of flexion is an indication of hypermobility of the lumbosacral spine. The patient gradually attains erect posture from flexion. This is achieved by reversal of lumbar pelvis rhythm, the movements of the pelvis on hip and lumbosacral spine. Derotation of pelvis occurs and lumbar kyphosis changes to lumbar lordosis. Normal range is 80 degrees.

Extension: From the erect stride standing posture, the patient is asked to extend the whole spine beyond midline to the maximum range (Fig. 32-38). This movement produces compression on the posterior vertebral bodies and facet joints with the opening up of the vertebral bodies anteriorly. It produces pain due to compression of the posterior structures. Normal range is 20–30 degrees.

FIG. 32-38 Spinal extension and its measurement by plumb line pointer.

Lateral flexion: A patient with knees straight is asked to bend the trunk to one side sliding his hand (finger tips) as near to the floor as possible from the lateral aspect of the leg. This movement compresses the tissues on the lateral side of the spine on the side of bending and causes stretching of the tissues on the contralateral side. If flexion towards the painful side aggravates the pain, the lesion could be either due to intra-articular pathology or a disc lesion lateral to the nerve root. If lateral flexion away from the painful side increases pain, then the lesion may be articular or muscular in origin; disc protrusion, if present, is likely to be medial to the nerve root. Normal range is 40– 45 degrees (Fig. 32-

FIG. 32-39 Lateral flexion of the spine and its measurement by sliding ruler arrangement.

Rotation: Rotation is tested with the patient lying on the side or sitting with the hip and knee in flexion. The movement is tested on both sides (right and left). The site of pain is noted, and is assessed in relation to the other movements tested earlier.

Diagnostic physical tests

The data collected from history and physical examination are correctly interpreted. Specialized diagnostic neuro-musculoskeletal tests can be done whenever necessary to arrive at the exact diagnosis.

https://telegram.me/aedahamlibrary

Presence of sciatica: If there is unilateral trunk deviation giving rise to sciatica during trunk flexion, it is a diagnostic sign of possible unilateral disc protrusion. When the disc protrusion lies in the axilla of the root, the trunk is deviated towards the painful side, whereas if the protrusion lies lateral (shoulder) to the nerve root, the patient will try to prevent further root compression by deviating away from the painful side (Fig. 32-43).

Straight leg raising (SLR) or Laseque’s sciatic nerve test: It is one of the important diagnostic tests. It is a protective reflex test which causes traction on the sciatic nerve, lumbosacral nerve roots and dura mater. It is a passive test done in supine position (Fig. 32-44). Appearance of pain in the distribution of the sciatic nerve up to 45 degrees of hip flexion with extended knee indicates positive SLR test. If the pain thus felt is aggravated by passive flexion of the neck and passive dorsiflexion of the foot, it is a ‘positive neural sign’ or positive SLR. The real stretching of the inflamed dura is possible only with all these three manoeuvres. While conducting SLR test, it must be remembered not to confuse it with hamstrings stretch due to straight leg raising, especially in patients with tight hamstrings confirmed by dull pain over the posterior aspect of the knee joint.

Treatment

Physiotherapeutic modalities in the management of low back pain

A number of studies have been reported to find out the most effective modality in the treatment of idiopathic LBP. None of the studies so far has proved the definite superiority of a particular modality. The objective findings of various studies can be summarized as follows:

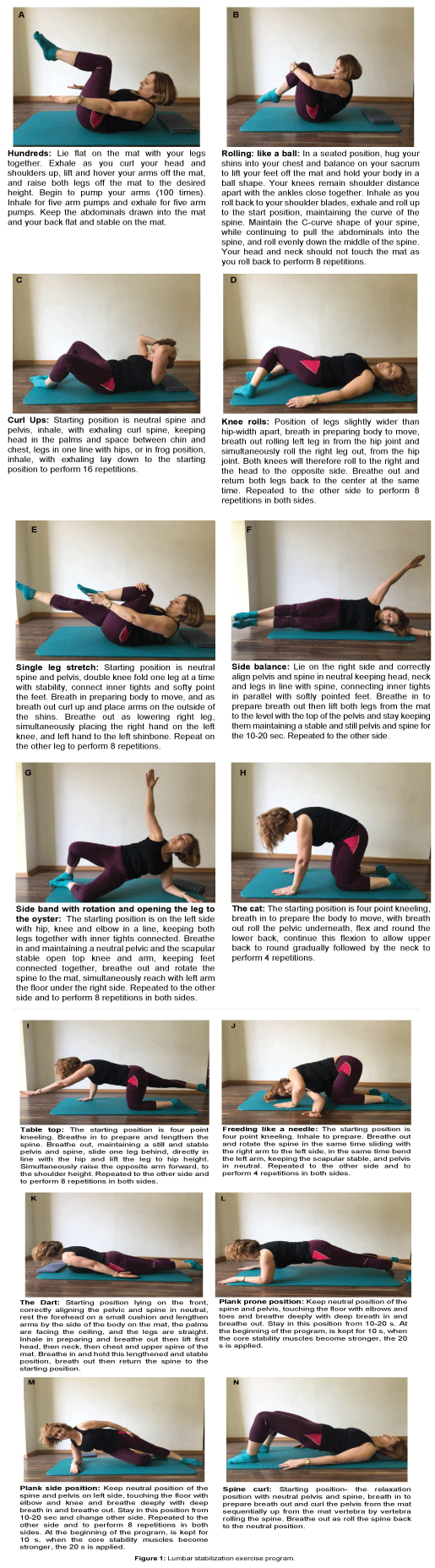

1. Properly controlled exercise programme is a common effective modality with any of the therapeutic approaches.

2. Manipulation has a definite edge over the other approaches in selective cases.

3. Maximum benefit was observed in patients treated early (within the first month of the onset).

4. Postural guidance during rest and at work (back ergonomics) is very important.

5. The results are better in patients treated with a combination of more than one approach, rather than those treated with a single modality.

The following modalities, single or in combination, are generally employed in the conservative management of LBP:

1. Spinal exercises

2. Physical agents

3. Spinal traction

4. Role of lumbar spinal supports

5. Specialized techniques

Before discussing the rationale of each of these modalities, it is necessary to highlight the importance of ergonomic advice which consists of educating the patient on postural adaptations (static as well as dynamic) to reduce strain on the back.

Role of spinal exercises

A great deal of controversy still exists regarding the exact indication and the type of exercise for a particular aetiology of LBP. Specific optimal regimen of exercise is nonexistent. If the purpose is reduction of pain, exercise should be limited to the point of discomfort. However, if the purpose of the exercise is to regain mobility, the movement has to be carried well into a perceptible pain and maintained in spite of little discomfort; it should be performed often and be progressive. The exercise programme aims to:

1. decrease pain,

2. strengthen weak muscles,

3. improve endurance of muscles,

4. decrease mechanical stress to spinal structures,

5. stabilize hypermobile structures,

6. improve posture,

7. improve mobility and flexibility and

8. improve fitness level to prevent recurrence.

Effects of exercises

1. They increase strength of bones, ligaments and muscles.

2. They improve nutrition to joint cartilage, including intervertebral disc.

3. They enhance oxidizing capacity of skeletal muscles.

4. They improve neuromotor control and coordination.

5. They increase the level of endorphin in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood, which is found to be reduced in patients with LBP. Endorphin has been proved to have a significant pain-modifying effect.

6. Exercises have tremendous psychogenic effects and reduce the symptoms of depression and anxiety. 7. They promote the feeling of well-being, as there is an increase in the alpha wave activity, producing central and peripheral relaxation and decreasing the muscle tension (Colt, Wardlao, & Frantz, 1981; De Vries, 1968; Edgerton, 1976; Farmer et al., 1978; Fraioli et al., 1980; Hammand and Froelincher, 1986; Tylor, Sallis, & Needle, 1985). Exercises have been shown to be more effective than a dose of meprobamate in decreasing muscular tension (De Vries, 1968), in addition to their positive response in inducing sleep. Supervised activation, sometimes even beyond the pain limit but with controlled biomechanical activities, seems to be a more effective modality than any other therapeutic procedure .

The exercise programme should be minimal and as specific as a drug needed in proper dosage. The authors feel that it is high time to develop a scientific approach rather than blindly treating all patients of backache with hyperextension exercises. It is important to understand the effects of a particular type of exercises on the spine and its periphery. It is also highly improper to hand over one standard manual of back care and home exercise programme to all the patients irrespective of the cause of LBP. 1.

Flexion exercises: Williams (1965) advocated trunk flexion exercises for the following aims:

(a) To open the intervertebral foramen and facet joints, reducing compression on the nerves.

(b) To stretch (tight) back extensors, reducing stress on the lumbar spine.

(c) To strengthen abdominal muscles.

(d) To increase endurance of abdominal muscles.

(e) To free posterior fixation of lumbosacral articulation.

(f) To protect the lumbar disc from excessive posteroanterior pressure through the development of intra-abdominal pressure (Bartelink, 1957; Morris, Lucas, & Bresler, 1961).

However, internal and external oblique muscle groups have been found to be instrumental in generating the reflex intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). They also have an added advantage of avoiding range of true flexion, and hence need special attention.

Caution It must be remembered that the excessive participation of the rectus abdominis and obliques results in compressive forces, and hence are to be avoided (Valsalva manoeuvre). Graded shoulder lift sit-up with rotation of the trunk in hook lying position is the ideal exercise to emphasize the action of oblique muscles (Fig. 32-54). Flexion without rotation strengthens the rectus abdominis (Figs 32-55A,B and C). Graded holding of knee–chest position (Figs 32.55D and E) stretches tight spinal extensors responsible for exaggerating the lumbar lordosis.

A

B

Contraindications

1. In acute disc prolapse, as exercises exert excessive load on the lumbar discs and open the posterior intervertebral space.

2. After prolonged rest, when the disc is hyperhydrated, it is more susceptible to injury (Nachemson, 1980).

3. When the postural LBP is due to posterior pelvic tilt.

4. In the presence of a lateral trunk shift/list

5. In patients with osteoporosis, where incidences of compression fractures and wedging have been reported (Sinaki & Mikkelsen, 1984), as these exercises will increase compressive forces on the vertebrae.

2. Extension exercises: Effects of extension exercises are as follows:

(a) They promote normal physiological lumbar curve of the spine, allowing it to withstand axial compression force (Kapandji, 1979; White & Punjabi, 1978), thus facilitating lifting loads.

(b) They improve the motor recruitment, strength and endurance of the extensor muscles of spine and hip (Sinaki & Mikkelsen, 1984).

(c) In postural LBP patients, where the extensors develop tightness due to the prolonged flexion attitude of posture in sitting or standing position.

(d) They unload the disc and allow the fluid influx; therefore, important in patients with suspected posterior or posterolateral discs.

(e) They are the main muscle groups in postural holding and in the eccentric control of trunk flexion (Pauley, 1966). (f) They improve the mobility of the spine.

(g) They improve tone in the extensor muscles, which is often reduced because of the maximum natural flexion attitude of the human body.

https://telegram.me/aedahamlibrary

(h) Rare incidence of LBP in patients with strong extensors (Davies & Gould, 1982), and decreased endurance in patients with LBP suggests the important role of strong extensors (De Vries, 1968).

5. Stretching exercises:

These are of two types:

(a) General stretching exercises

(b) Specific stretching exercises

(a) General stretching exercises: They offer stretching to all the soft tissues and the spinal joints which remain contracted when one type of posture is sustained for a long time. Generalized stretching is needed to avoid adaptive shortening of the soft tissues, good posture, mobility and, above all, the feeling of well-being and alertness.

(b) Specific stretching exercises: They are of special significance when the basic cause of LBP is the adaptive soft tissue shortening. Long sessions of low intensity sustained stretching techniques may be required.

6. Self-correction and its maintenance:

Proper and adequate education on self-corrective techniques of incorrect postural habits may be necessary. Maintenance of the postural self-correction forms an important part of this technique. 7. Exercise specificity: Once the type of exercise has been selected, the specificity has to be decided on the basis of the findings of examination. The exercise must not be PAINFUL. The major types of exercise techniques are as follows:

(a) Isometric

(b) Isotonic

(c) Isokinetic

The efficiency of the selected exercise technique is to be checked at regular intervals.

8. Aerobics:

Gradual introduction of aerobics is proving extremely effective in the control of LBP. These should be started gradually so that there is no undue strain. Activities such as brisk walking, jogging, swimming, cycling, rope jumping and dancing have been found to be very useful in controlling as well as preventing LBP. They need to be supervised and controlled biomechanically by the physiotherapist. They must begin with relaxed free movements of the whole spine.

Physical agents

Various types of physical modalities can be applied as adjuncts in the treatment of LBP. Selection of a modality depends upon the mode of action of the modality to suit symptomatology and the nature of tissue involvement. The objectives of using various physical agents are as follows:

1. To control pain and spasm.

2. To reduce inflammation.

3. To facilitate the use of specialized techniques such as mobilization, traction and exercise.

4. To reduce depression, tension or any other psychological factor.

The various physical agents are discussed below.

1. Ultrasound: Ultrasound has been in use since the 1950s and is definitely advantageous in the following situations:

(a) It can be given in acute as well as chronic phases of LBP.

(b) It can be used for driving the medications such as hydrocortisone and xylocaine into the skin over the targeted tissues by phonophoresis.

(c) It increases cortisol present in the spinal nerve roots and lumbosacral plexuses, thereby improving mobility by decreasing pain (Touchstone, Griffin, & Kasparow, 1963).

(d) It increases extensibility of the connective tissues such as tendons and joint capsules (Lehmann, 1970).

This particular action of ultrasound is important, as it can improve the accessory movements in the apophyseal joints. Therefore, it is ideal before applying mobilization techniques.

(e) It has been found to reduce spasm in lumbar radiculopathy (Clarke & Sterner, 1976). Although the dosimetry of ultrasound is based on tolerance, an output intensity of 1.5 W/cm2 with continuous mode of application for a period varying from 5 to 10 min is a standard pulsed ultrasound ideal for acute LBP.

2. Cryotherapy: It is a simple and effective procedure which reduces muscle spasm and inflammation in the acute phase. Ice massage with ice cubes for 3–5 min or with ice bag for 15 min can be used directly over the painful areas; it also acts as an analgesic and provides the most needed compulsive rest.

3. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation: Transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS) over the trigger points or acupuncture points has been reported to be effective in both acute and chronic conditions (Ersek, 1976). It reduces the perceived pain by:

(a) elevating endogenous opiate levels in the brain and spinal cord (Bonica, 1979), and

(b) continuous stimulation of cutaneous afferents which blocks pain in the substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord (Melzack & Wall, 1965).

https://telegram.me/aedahamlibrary

Frequency of 2–4 Hz, output intensity of 50 MA, pulse rate at 2 pulses/s and pulse width between 30 and 60 min have been reported to be an effective mode of application in chronic as well as acute conditions.

4. Moist heat: Moist heat in the form of hydrocollator packs reduces pain and spasm in the acute phase. It can be used as an effective adjunct before applying specialized techniques or even before TENS, short-wave diathermy (SWD) or ultrasonics because of the comfortable heat along with forced rest for a longer period.

5. Electroacupuncture: It has been reported to be an effective pain controlling modality but needs special equipment. It also needs specific knowledge of the theory of acupuncture and is difficult to practise as a routine therapy (Santiesteban, 1980).

6. Diathermy: Diathermy is preferred for deep heating of the tissues over larger areas. However, drum electrodes or induction electrodes can be used where superficial heating is advisable (Griffin & Karselis, 1978). Of the two modes of diathermy –

(a) continuous and

(b) pulsed or nonthermal – the latter is ideal in dealing with acute conditions or after surgery. In chronic LBP, a continuous modality is preferred. Various new modalities such as interferrential currents, diapulse, megapulse and laser beams are added to physical therapy. Helium–neon laser has been reported to be significantly effective in the control of back pain with musculoskeletal trigger points (Synder-Mackler, Barry, Perkins, & D’Soucek, 1989).

7. Electrical stimulation: High intensity electrical stimulation over the trigger area may respond favourably, especially in LBP of psychogenic origin.

8. Massage: Gentle soothing massage is instrumental in reducing local muscular spasm. It helps in removing nociceptive substances by improving blood circulation. It also gives a feeling of betterment by inducing relaxation. The efficacy of a particular modality should be evaluated periodically during the course of treatment. The selection of a particular physical agent should be done as per the underlying pathology.

9.Spinal traction

It is a popular modality in the management of LBP. Range of traction force: There exists a great deal of variation in the spectrum of the effective traction force. To overcome the force of friction, a force equivalent to the body weight is necessary. Therefore, the traction force required to produce distraction in the vertebrae ideally should be of at least half the body weight. The range of traction force may vary from 37 to 91 kg (Hickling, 1972; Judovich, 1955; Mathews, 1972). As a result of traction, the range of vertebral distraction as reported in various studies varies from 0.3 to 4.0 mm. The maximum distraction reported is 2.0 mm (Harris, 1960).

Spinal manipulation

Manipulation is a very specialized technique which involves skilled, gentle, precisely passive movements of a joint either

within or beyond its active range of motion by manual force. A small and firm but gentle force is applied to restore the lost movement by producing a desired ‘joint play’ or to achieve unlocking. It can be carried out successfully only by thorough training and practice based on sound knowledge of the neurophysiological and biomechanical processes as applied to a specific joint and its movement.

A beginner should undertake manipulations only under supervision of an experienced colleague. Unskilled attempted manipulation on the basis of theoretical knowledge alone can be disastrous. The aims of manipulation are to:

1. relieve pain

2. promote increased function Effects of joint manipulation

1. Mechanical: It improves the extensibility of the connective tissue elements of the capsule, ligament, muscle and fascia.

2. Neurophysiological: It blocks the centripetal transmission of nociceptive (pain) pathways through sensory input, which could be cutaneous, muscular, articular or auditory.

3. Sensory stimulation: Skilled evaluation of the joint mechanics and soft tissues itself provides enough sensory stimulation and encouragement to the patient.

Indications of manipulation

1. Vertebral malposition

2. Abnormal vertebral motions

3. Abnormal joint play or end feel

4. Soft tissue abnormalities

5. Muscle contracture or spasm

6. Severe nerve root pain

7. Chronic spondylotic changes

8. Chronic discogenic pain Techniques:

There are four basic techniques.

1. Oscillation technique: It is employed in a recently injured joint where minimal movement is indicated to retain its function.

2. Stretch technique: Joints presenting restriction due to capsular or myofascial changes are benefited by ‘stretch manipulations’.

3. Thrust technique: Joints demonstrating sudden hard stop to a movement in one direction due to adhesions will respond better to a thrust technique.

4. Rotation and side bending technique: When there is restriction of the facet joint mobility. During the movements of forward, backward or side bending, the facets slide on each other. During rotation, the facets distract from each other.

Restrictions in the mobility of lumbar facet joint instantaneously respond to rotation and side bending manipulation techniques (Haldeman, 1983; Maitland, 1977; Paris, 1983).

Contraindications

1. The most important contraindication is the unskilled manipulator

2. Patients with prolapsed disc (acute discs with advancing neurological signs)

3. Instability, spondylosis and fracture

4. Fever, influenza, rheumatoid arthritis

5. Active inflammatory joint disease

6. Advanced osteoporosis and diseases of bone

7. Bleeding disorders

8. Pregnancy Support modalities such as heat, massage, ice, ultrasound and TENS relax the soft tissues and may be used as an effective adjunct before and/or after manipulation.

Treatment of idiopathic low back pain

In idiopathic LBP, it is necessary to recognize the nature of the LBP syndrome.

It may be static or dynamic; static when pain is present during stationary position, and dynamic when it appears during movements. The complex nature of the origin, symptomatology, the individual’s perception of pain and its overall influence lead to marked variation to the therapeutic approach. The basic therapeutic regimen during the acute and subacute stages is outlined as under.

Genuine content.. Was really helpful.

ReplyDeleteWrite more.. ☺

thanku .i will work more on this

ReplyDeleteIt's more informative and detailed content

ReplyDelete